Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

When I met Rachel in Jerusalem for the first time, we were sitting in a coffee shop overlooking the walls of Jerusalem’s old town. But our minds were in Dobrushka, a small town in the northwest of the Czech Republic. There she had taken a Czech language course. I noticed a kind of sadness in her voice when she said: “When I was there, I looked around and thought: ‘This could have been your home!’”

The reason why she said this is her father, the Czech Israeli pilot Joe Alon. Originally, his name was Josef Placzek, who was shot while completing his mission in Washington. “I lost my father when I was only five years old. He was the military attaché of the Israeli Air Force in Washington between the years 1970-1973 and was 44 years old when he was murdered. After his death we – my mom and my two sisters – came back to Israel, where we lived in a village for the families of the Israeli pilots.”

Rachel fondly remembers that time: “The streets were named after different birds: Eagle street, Nightingale street, Lark street… All the children were pilot’s children and we were all good friends. We had an open house. Every Friday evening my mom lit the candles on the festive table. The big feasts we celebrated at our mother’s brother’s or sister’s place.

When I turned 18, I wrote a letter to my uncle in Australia asking about my dad. Uncle David was his brother. I wanted to learn something about my father’s childhood and youth. A great relationship developed between us that lasted until his death.”

The pioneers from Kibbutz Bet Alfa

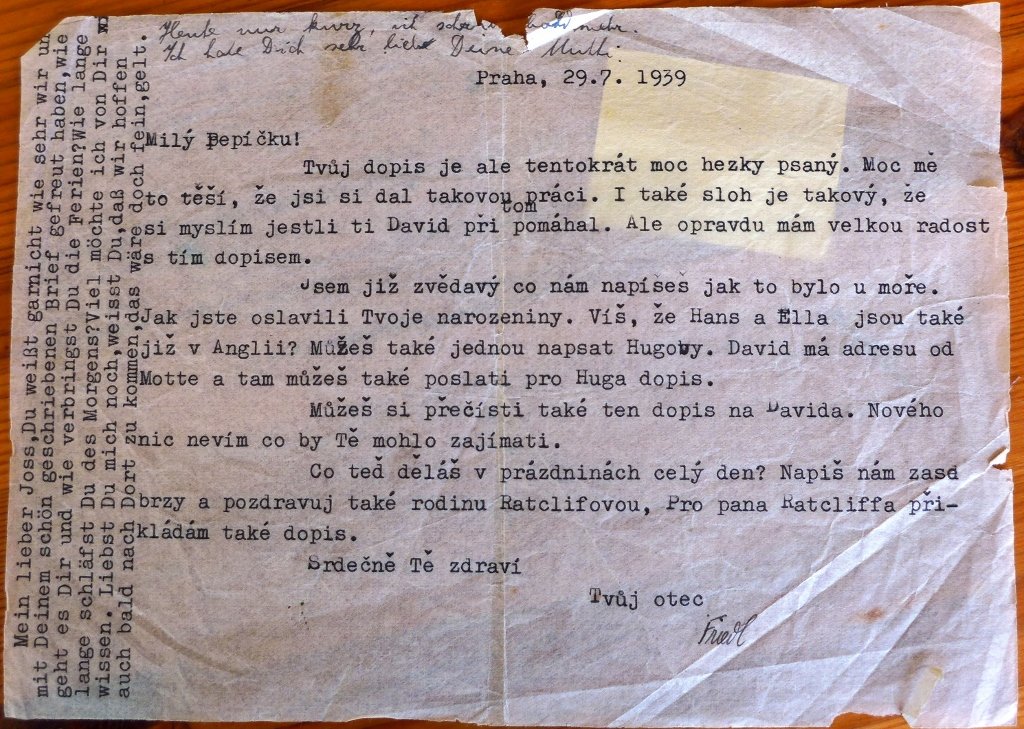

The next time Rachel and I sat over yellowed letters from her paternal grandparents that she had received from her Australian uncle. Most of these letters are in German, some in Czech and some in both languages. Together we try to find more pieces of the puzzle of the tragic fate of Tekla from Paderborn and Siegfried from Hustopetsh.

The two met in Kibbutz Bet Alfa in the valley of Jezreel. In spite her parents’ opposition, Tekla, a young Zionist, decided to leave Germany where anti-Semitism had noticeably increased. Siegfried, called Friedel, was full of communist ideals about building a new, just society in the Jewish homeland, which the Balfour Declaration promised to Jews in the British Mandate of Palestine.

“My grandparents were pioneers,” Rachel says proudly. They had come to the valley at Jezreel “at the foot of the Gilboa Mountains, hoping to convert the stony slopes and marshy lowlands into blossoming orchards and fertile fields”, David Placzek wrote in his Memoir.[1]

David and Josef were born in the kibbutz. After only eight years, in 1930, Friedel decided to move his family back to Europe. He was disappointed with the situation. Rachel’s father, Josef Placzek, was just two years old at that time.

Back to Europe

It was not easy to find work. Finally, the family settled in Teplice, where Friedel worked in the council of the German-speaking Jewish community. The boys, who had previously known Hebrew and German, now spoke Czech and went to a Czech school.

David writes in his memoir that his father believed that the best way to solve the ‘Jewish question’ was through integration and assimilation into Czech society: “To demonstrate the strength of his convictions, all our family documents stated that we were of Czech nationality, although Czechoslovakia was one of only a few countries that recognized the Jewish nationality officially as an option.”[2]

After the Nuremberg Laws were implemented many of Tekla’s relatives left Germany. They tried to convince Friedel to come back to Palestine, but in vain. In the border area between Czechoslovakia and Germany where the Placzek family lived, were daily clashes between Czechs and Germans. Even though Rachel’s grandfather was a staunch communist and taught his children at home that religion is opium for mankind, the whole family went to the synagogue because of his job. David reached the age of religious independence, learned to recite his weekly portion from the Torah scroll and celebrated bar mitzvah. That was the last bar mitzvah in the synagogue in Teplice. Then the German army invaded and the synagogue was destroyed.

The family fled to Prague together with many others. From there they tried to find a way to escape, but it was already too late. The last known letter is from 1941. After that, both parents were sent to the concentration camp of Theresienstadt and from there on to Auschwitz. They managed to send their sons in time to England on the so called ‘Kindertransport’.

In 1939 Tekla wrote the following lines to her son: “My dear Joss! You don’t even know how happy we were with your beautifully written letter. How are you and how do you spend your holidays? How long do you sleep in the morning? I would like to know a lot about you. Do you still love me? Do you know that we hope to come there soon too? That would be nice, wouldn’t it? I love you very much, your mom.”

Next to Josef and David, Friedel’s brother, Uncle Oskar, was the only one of the Placzek family who survived Theresienstadt. David and Josef reunited with him again after the war.

After the war to Israel

Back in Czechoslovakia Josef completed a pilot course together with his friend Hugo Meisel, who later changed his surname to Marom. Both were determined to support the newly born state of Israel, which was fighting for its very existence in the War of Independence. Both made history as founders of the Israeli air force. In Israel Josef met his wife Dvora, who had worked as a nurse in Beersheba.

Rachel’s black, curly hair and dark skin reveal the genes from her mother’s side: “My mother was born in Yemen. After my parents got married, she stopped working in the hospital. Because my father had lost his home as a child, she always wanted to be there for him. She cooked traditional Yemeni dishes, but also learned Ashkenazi food, such as ‘gefillte fish’. Furthermore, she even learned to make Czech dumplings with baked goose and red cabbage.”

The Czech and the Australian Placzeks

Rachel once decided to visit Prague together with her sister and their husbands. They also let their cousin in Australia know about their plans. “He then told us that a daughter of our Czech cousin had contacted him because she was searching for some relatives. He knew that they had a coffee shop, the ‘Café Placzek’ in Brno. So, we decided to visit Brno and took some photos with us. At our very first meeting, the Placzek family also took out old albums and after a few minutes we were one happy big family.”

David had married Irena, Jiří had married Jiřina. Therefore the Placzeks are no longer Jews. Only those with Jewish mothers are considered Jewish. “But blood is not water!” says Rachel. “We’re cousins and I don’t care that they’re no longer Jews!” Her voice sounds a bit excited when she returns to the same topic: “Yes, I do care. But I am not blaming anyone who left Judaism after the Holocaust. I know people who to this day refuse to enter the database of the Diaspora Museum to search for their roots. They don’t want to be registered as Jews anywhere. We know what these kind of lists caused!”

The Czech course in Dobrushka

With the help of the Association of Israeli Friends of the Czech Republic Rachel later discovered that there was a possibility to enroll for a Czech course. “I jumped into it headfirst. I wanted to get to know my roots, which in my opinion have been cut off too early.” During the bus ride she was touched by hearing the language she used to know from her father. “I looked out of the window and thought: ‘Were there any Jews hiding in this forest?’”

“After three days of gloomy thoughts I asked myself whether I wanted to concentrate on what no longer exists or on what does. I knew the ‘not anymore’ from an early age – there was neither grandma nor grandpa and I had lost my father too. Then I decided to make the best out of my family history in relation to the Czech Republic, the course and the Czech language.”

Rachel continues: “I think that for those who grew up with a trauma or challenges in their childhood a little piece of something good is a big deal. Those who have a simple and comfortable life are more likely to become depressed. Life is full of challenges, difficulties and problems. And we have a choice – depression or discovering the good.”

Rachel studied literature and founded a private publishing company “Tfarim.” There she captures the life stories of Israelis. “Because I write down stories of old people who find it difficult to get out of their chairs and offer a glass of water, I know that being able to get up and walk or have a coffee with sugar is a big deal. It’s not easy to convince someone of this, but I think that you can practice it: In the evening I just think about what good thing happened to me that day.”

After she made this decision, Rachel began to enjoy the course and to feel at home in the Czech Republic. “And guess what, the people there look you straight in the eye. I’ve traveled a lot. In some places people turn away thinking that you want something from them or even want to harm them. In Israel, people look straight in the eyes too. I like it, that’s nice and friendly.”

The Joe Alon connection

During that course Rachel had the idea to organize a student’s exchange between Israel and the Czech Republic. “I wanted to pass on something from what I’ve got. I am not a teacher, but I enjoy giving information and explaining. So I came up with the idea of taking tenth grade students before they graduate from high school and in our country the army service begins, and to build on what unites us – our shared history, including military aid in the War of Independence and also on shared humanism.”

“Jews, who were born before the state of Israel came into being, see Israel as a miracle that must be built up and preserved. I was born into a completely different situation than my parents and grandparents. Of course, there is always something to improve, but we have our own home.”

This student’s exchange is called in Hebrew: “Joe Alon’s study program for bringing hearts closer.” Despite the cultural differences, which can already be seen in the title of this project, hearts grew closer and the Czech students were delighted. Recently, the pandemic has made it impossible for Israelis to visit the Czech Republic.

[1] David Placzek, Memoir (Jerusalem, Israel: Tfarim Publishing, 2016), 13.

[2] David Placzek, Memoir (Jerusalem, Israel: Tfarim Publishing, 2016), 20.