Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Israel became an occupier with the Six-Day-War during the first days of June 1967. Thus, or somewhat similar, it seems from a present perspective, considering current axioms commonly accepted concerning a solution of “the” Middle East conflict between Israelis and Palestinians. Accordingly, there is talk about “the borders of 1967” when the lines that separated the Gaza strip and West Bank before 1967 from the Jewish State of Israel are the issue.

From 1949 until 1967 the Gaza strip was administered by Egypt, however, never annexed. During the same time, the West Bank was under the rule of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. On April 24, 1950, King Abdallah I formally annexed these disputed territories. This annexation was never recognized by neither the UN nor the Arab League, except Great Britain and Pakistan. In retrospective 1967 somehow feels like the birth year of the idea of two states for two peoples as solution of this conflict and the somewhat ideal end of the Israeli occupation of “Palestine”.

True, already the UN Resolution 181 of November 29, 1947 saw the solution of the Palestine problem in the creation of two entities, an Arab and a Jewish state. Likewise true is that the political representatives of the Jewish population of what was then the British Mandate of Palestine accepted this “Two-State-Solution” – even though they were not really excited about it. All Arab leaders who had a say at that time on the other side rejected the United Nation’s separation plan of November 1947, just as they had rejected all its predecessors, including the suggestions of the Peel Commission of 1937, which might be seen from this perspective as mother of all Two-State-Solutions. The UN Resolution 181 became historically unique in as far as its implementation was answered by a whole community of states with war.

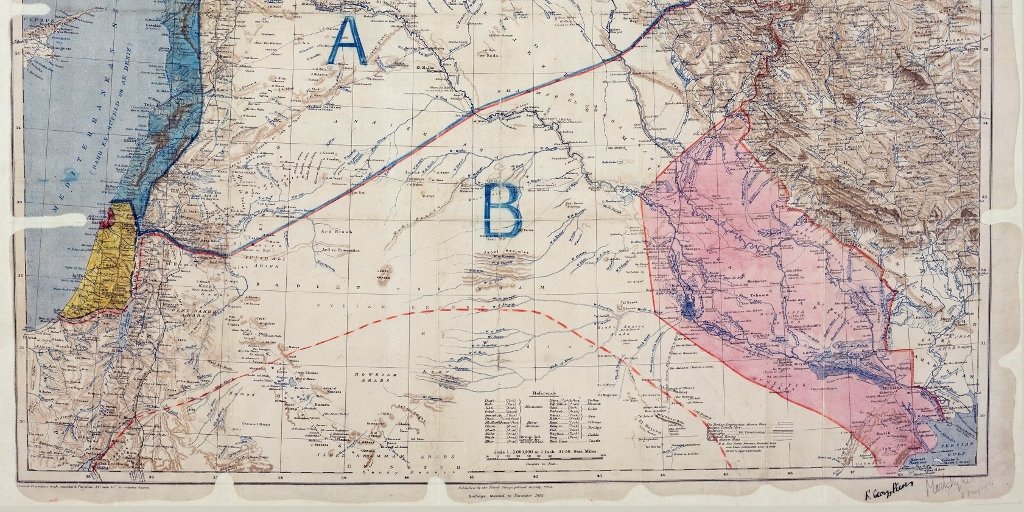

Before 1937 there had been hardly any talk about dividing the territory between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea into two states. The impression of Britain’s dividing its mandate of Palestine in 1922 might have been still too fresh. At that time, the British had given more than 75 percent of the territory to the Hashemite Emir Abdallah and called it “Transjordan”, even though it had been originally entrusted to them by the League of Nations in order to create a Jewish homeland – not to divide it. In April 1920 the Conference of San Remo, as a result of the Treaty of Versailles, had already divided between Arabs and Jews what remained of the Ottoman Empire in the Levante, Mesopotamia and the Arab Peninsula.

Emir Faisal, Abdallah’s brother, as representative of his father Hussein, the “King of the Arabs,” had then agreed to a Jewish homeland in Palestine. In his famous exchange of letters with Chaim Weizman, leader of the Zionist movement, he even promised on January 3, 1919, to “to encourage and stimulate immigration of Jews into Palestine on a large scale”. At that time “Palestine” included not just the territory of today’s Israel and the Palestinian Authority, but also the whole of what is today the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. The Faisal-Weizman-Agreement enthused about the “racial kinship and ancient bonds existing between the Arabs and the Jewish people” and promised “the closest possible collaboration in the development of the Arab State [on the territory of today’s Syria, Iraq, Jordan and Saudi Arabia] and [a Jewish!] Palestine”.

But: Is this relevant at all for a consideration concerning the current discussion of a Two-State-Solution? – For the United Nations, certainly. In spite of all national aspirations, like those of the Kurds, the UN cling to an order of states, that was imposed upon the Orient by the victorious powers after World War I. The decisions of the European politicians at the beginning of the 20th century were also highly relevant for those fighters of the so called Islamic State (ISIL or ISIS) who proclaimed “the end of Sykes-Picot” when they destroyed not too long ago the border demarcations between Syria and Iraq. Finally, 90-year-old settler leader Elyakim HaEtzni alludes to them when justifying his life in Kiryat Arba near Hebron from a legal point of view: “On the basis of the decisions of the League of Nations I, as a member of the Jewish people, have a right to settle in Palestine. This right cannot even be denied by a Jewish State of Israel.”

Considering the feelings and way of thinking of those people, who are immediately impacted by the discussion of a Two-State-Solution, Jews and Arabs alike, the historical developments of the past one hundred years are highly relevant. The rejection of any Two-State-Solution by the Arabs in the years 1947 through 1949 is strongly present in Jewish as well as Palestinian thinking until today. It was the Arab negotiation partners who prevented the use of the terminology “borders” for the ceasefire lines in the ceasefire treaties on Rhodos early in 1949, because they refused to recognize a Jewish state in whatever borders. From 1949 until 1967 all of the territory that today according to the international community should be reserved as “Palestinian territory” for the creation of a “State of Palestine” was in Arab hands – either administered by Egypt, or annexed by Jordan. As far as I know, nobody demanded the creation of a Palestinian state during this period of time, certainly not “side by side” with the Jewish State of Israel.

Today, representations of the development of a Two-Sate-Solution refer to the agreements of Madrid and Oslo, as well as to a whole series of UN resolutions starting at the end of the Six-Day-War: None of these legally binding documents speaks about “two states for two nations.” Already the agreement of Camp David, that sealed the peace between Egypt and Israel on September 17, 1978, promised just an autonomy to the Palestinians, but not an independent state of their own.

Joel Fishman[1] of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, a think tank that is Netanyahu friendly, sees any Two-State-Solution as instrument of a political “Salami tactics”. Arafat’s companion Salah Khalaf alias “Abu Iyad” adopted it during a visit to Hanoi in the 1970ies from the North Vietnamese. The northern Vietnamese communists reached the goal of this strategy in 1975 when the last American soldier fled by helicopter from the roof of the US Embassy in Saigon. According to Fishman any Two-State-Solution would be “politicide” – political suicide – of the Jewish State of Israel.

Israelis who still emphasize, that a Two-State-Solution is in the best interest of the State of Israel, that Israel’s character as Jewish and at the same time democratic state cannot be protected otherwise, have one goal only: To get rid of the Palestinians, and especially of Israel’s responsibility for them. Half a century ago ethnic cleansing would have been acceptable to worldwide public opinion as solution for ethnic and territorial conflicts. Today this is out of question. Therefore, there seems only one solution: The creation of a state in which the Palestinians are able to determine their own fate by themselves.

However, what even the most Palestinian friendly Israelis are willing to offer their neighbors as “state”, is inacceptable as “state” even to the most dialogue minded Palestinian nationalists. Even those Israelis who cling to a dream of a Two-State-Solution and therefore enjoy hardly any backing in their own society, in the best, most generous case offer to their Palestinian neighbors an autonomy, that can be called “state.”

To the point: Nobody who knows the political situation in and around Israel and pursues a prospering, secure and Jewish Israel is able to imagine a “Palestine” with an air force like Israel; a “Palestine” with a naval fleet like Israel; a “Palestine” that manages its own air space or electronic sphere as if there were no Israel. In the foreseeable future “Palestine” will never be really sovereign side by side with a Jewish Israel, for example, concerning its external borders, nor will it be able to freely determine its own foreign policy, e.g., invite its Iranian friends for military training in Ramallah in a similar way, Israel performs military exercises with Germans or Americans in the Negev.

From an Israeli point of view, the formula “land for peace” which is one of the basic ideas of the concept of a Two-State-Solution has been led ad absurdum during the past years. Actually, the Jewish state has not gained peace for any piece of land from which it retreated during the past decades, but only rockets and other security related challenges. This is true for the Sinai Peninsula which it returned to Egypt in the early 1980ies. This is true for Southern Lebanon from where Israel retreated in spring 2000. And this is true for the Gaza Strip, from where Israel evacuated all Jewish settlements in 2005.

Likewise, on the Palestinian side there is hardly anybody who pursues a viable Two-State-Solution. As early as 2006 the Palestinian electorate voted with overwhelming majority for the radical-Islamist Hamas, for whom the recognition of a Jewish state on any Islamic ground is in principle inacceptable. Even secular, Hebrew-speaking, cosmopolitan Palestinians express complete unashamedly their view: “The crusaders where two hundred years in Palestine. The Jews will not rule here for such a long time.”

The question is not, whether from a Western point of view, in the framework of Western thinking and on the basis of a Western logic a Two-State-Solution would be the best or even the only imaginable answer to the Palestinian-Israeli mess. All decisive would be, whether those who are directly and on the scene involved in this conflict will be able to recognize a Two-State-Solution as “their” objective, whether they are able to identify with it, and actively pursue it, even if this demands painful sacrifice for them. Up until know neither the Israeli nor the Palestinian side seems to be ready for this.

Therefore, it is idle to try to evaluate the Two-State-Solution from a European or American point of view. The West should finally draw its lesson from the Sykes-Picot agreement, that divided the Ottoman Empire towards the end of World War I into British and French spheres of interest and, thus, became the basis of the order of states that formed the Orient during the past century. A political order that was invented in the West can be implemented and kept alive in the Middle East only by means of dictatorships and, therefore, is doomed to failure in any case. The “Arab Spring” and its horribly bloody fruits are the best evidence to this.

Footnotes:

[1] “The Delusion of the ‘Two-State Solution’,” February 12, 2017: http://mida.org.il/2017/02/12/the-delusion-of-the-two-state-solution/ (21.7.2017).