Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

The Jews steal the land of the Palestinians. This accusation is present in all reflections on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Israeli settlers in Palestinian territory are the big obstacle to peace in the Middle East conflict.

Yossi Edri lives in Beit Haggai, a Jewish settlement on the southern edge of Hebron. He is at the forefront of this conflict. As a full-time job, Edri is responsible for the security of Jewish educational institutions covering an area of about 1,000 square kilometers: Kindergartens, schools, boarding schools, Talmud schools, and colleges preparing teenagers for the army.

In addition, he is a liaison officer between the army and the civil administration in the Israeli settlements of the southern Hebron hills. Furthermore, he spends a lot of time acquiring land from Palestinians for the Jewish people.

Endless fight

With difficulty the heavy Land Rover torments itself over the stony ground through the dusty, hot wasteland. It’s not just the equipment – radios, weapons, ammunition, rescue and medical equipment – that gives the vehicle its above-average weight. The dark green off-road car is protected by heavy metal plates in the doors. The windows are one inch thick and bulletproof.

Superficially, the southern Hebron mountains, the transition from the Judean highlands to the infinite Negev desert, are a hostile, inhospitable area. This is true not only in terms of nature, but also for their people, society, and the political situation. Bedouin wrest with their herds a subsistence level from the barren landscape. Hyenas and vultures eliminate a corpse in no time.

For several years now every new field, every tent, every container and every shack has been an expression of the struggle between the nations who claim their existence here. Since Biblical times this mountain ridge between the Mediterranean Sea and the Dead Sea has been soaked over and again by the blood of those who aspire to settle it.

On closer inspection, however, this country and its people also have a charm. At least they are interesting. Nature offers a unique biodiversity. At the southern edge of the Judean Mountains, four climatic zones meet.

Red wine drunkards

The relationships of the people who live in this area are not one-dimensional. They cannot be simply schematized on “Israelis here” and “Palestinians there”. Just think of the cave dwellers who are to this day known by the Arab name “Hamra”. “Hamra” means freely translated the “red wine drunkards”.

Sometime around two and a half centuries ago, the Hamra left their homeland in the south of the Arabian Peninsula. Jews were persecuted in Yemen. In the Promised Land they arrived months later as “Muslims”.

To this day, some families of the Hamra ignite the traditional lights on Friday evening. The official Israel sees them as “Palestinians” and does not want to know anything about them, even though their name and their customs reveal that they belong more to a Jewish state than to the “House of Islam”.

Oriental customs

Yossi Edri reveals a perspective to the fact that below the rough shell of lawlessness a fine network of fascinating orders is functioning. He himself was born in Casablanca, on the Atlantic coast of Africa, just over five decades ago. Yossi speaks Arabic fluently. As a toddler, he immigrated to Israel with his parents.

Since coming to Hebron as a teenager, he has built a variety of relationships with his Arab neighbors. He talks about his youth with the children of Sheikh Ja’abari and how he accompanied Rabbi Levinger as translator and bodyguard to Hebron’s mayor Qawasme in the 1980s.

“For us Orientals, honor is the most important issue,” Yossi explains. “This is true not only for the Arabs but also for us Mizrahi Jews.” And: “If you touch an Oriental at the honor, he may give up all money. But he will take revenge, in a way you never dreamed of.” Europeans do not understand that.

European order

Abruptly the Land Rover stops at the top of a hill. From here you can see far into the country. But Yossi’s eyes are fixed on the ground until he finds what he’s looking for on a rock: A weathered hemisphere made of brass, inserted in a boulder.

In many places, the British have attached these survey points after they had taken over the rule of Palestine in 1917. A whole brigade of the British Army was engaged in land surveying, cartography, archeology, capturing the fauna and flora.

Based on these surveying points, the British cartographers recorded not only buildings but also elevation information, streams and old paths, all the way to the Roman roads.

The main reason for the British zeal to map everything under their rule was that they wanted to collect property taxes. From the locals, they asked not only the names of mountains and streams, but also for usages and property rights.

Ottoman law

In Ottoman times, all land belonged to the sultan. For the inhabitants there were only rights of usage. As far as these rights of use were recorded in property deeds – called “Qushan” – these were registered by the British. Natural forest, rocky terrain, desert and sea were never private but were “Mawat” land by definition – land of “the dead” – which yields no income. That’s why it could not be taxed.

Yossi is fully aware of the fact that these old records are only partially reliable. “If someone owned a plot of land of 150 dunams, often he registered with the British occupiers only 50 dunams als ‘Mali’[1] –as taxable area of use – although everyone in the village knew it was not true.” The key was to pay as little tax as possible.

In addition, the borders in Ottoman times were described with the help of natural clues: Watersheds, fountains and springs, streams, ruins or trees. Some of it has changed over time.

On foot, the steps were counted to calculate distances. Thus, contradictory information is not uncommon. But the question of who owns the land in this area is by no means arbitrary.

Old maps and property deeds

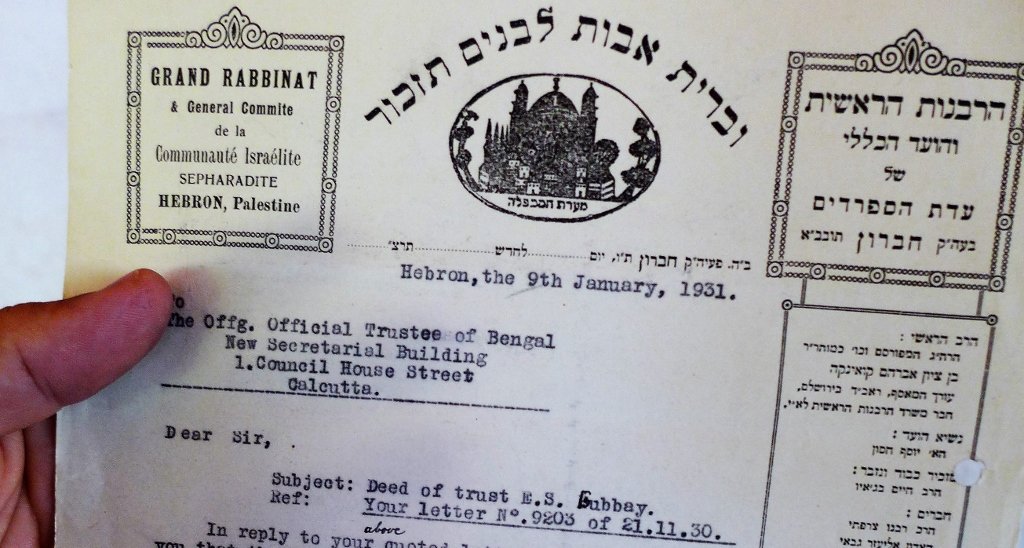

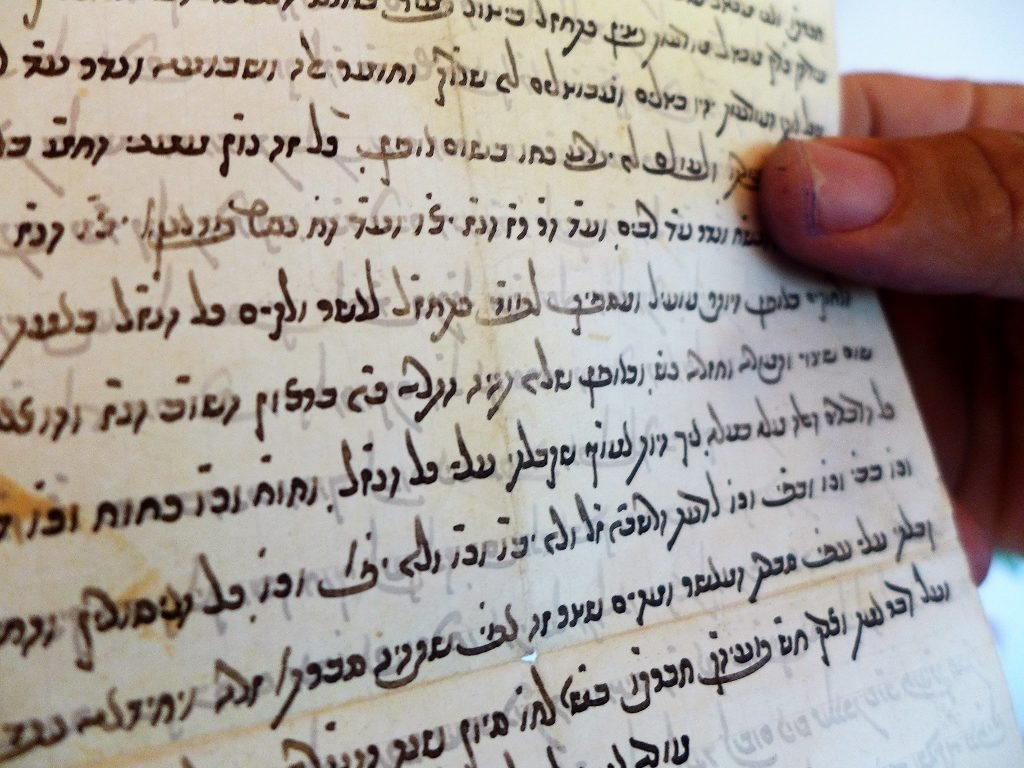

In his office, the Jewish land buyer pulls yellowed documents out of folders and plastic sheets, puts them on the table: “Here is the district Yatta noted… The Turks were pretty well organized in land issues…”

“Here, it is written: ‘I signed with my

thumbprint, according to the Islamic sharia’. And here you see how that was

confirmed in the British Mandate.”

It was mostly the British who noted down the land rights in this area. But even they did not really create a land registry.

Rule of the rich

Who was able to make such entries in Ottoman times? Usually people who could read and write: Scribes, scholars, clergymen, those who sat in the Sharia courts and the rich. Most of the people were illiterate, falachs, poor agricultural workers.

When a new “Qushan” was issued, the neighbors and the mukhtar, the mayor, had to confirm its correctness. Very much as it is described in biblical times, for example, in the fourth chapter of the book of Ruth, or in Jeremiah 32.

After all, it was the wealthy who had a special relationship with the Sultan in Istambul. That is how they came into the possession of the country. But even then, often only limited to a few years.

Land purchase today

“If we want to check the ownership of a particular property today,” explains Yossi Edri, “we first ask what kind of land it is.”

The first aerial photographs of this area were taken at the beginning of the 20th century by German pilots on behalf of the Ottomans. “Based on historical and new aerial photographs, we determine whether the land has been used for agricultural purposes in recent decades. Then the question arises: Was it state land? Is it in a land register somewhere?”

Who owns a property?

“If there is a land register entry, the Arab owner has won a world and can sell immediately, because then everything is clear.”

“If he comes with a ‘Malia’ – which roughly corresponds to an income tax return from Ottoman or British time – he must identify the plot of land exactly, produce a map, the correctness of which is then again confirmed by the neighbors.”

“So begins a process in which the authorities check everything. Only when the legal status of a piece of property has been determined correctly can we apply for a permit to purchase the land.”

Donations from Baghdad

Edri leafs through the old documents from Ottoman times, from the time of the British Mandate, from the Jordanians. “Here, Rabbi Suliman Mani purchased land in the early 20th century. The purchase was made with donations from Baghdad.”

“There is talk of Sheikh Tamimi from Hebron and Rabbi BenTzion Avraham Konika signing a document in 1931.”

The documents were written in Ottoman, Arabic and English, but also in Hebrew. “This is a document from 1928… Look, this grandfather lived from 1870 to 1935… and here the division of a heritage is documented.”

Equal rights for all

“There is a Supreme Court ruling in Israel that allows anyone to buy land anywhere under Israeli rule,” Edri expounds: “Everything else would be discrimination.”

“Ottoman, British, Jordanian and Israeli law are on our side in our efforts to acquire land. The dispute over whether Jews can buy land in the disputed areas of the West Bank is purely political and has nothing to do with legal issues.”

Land theft

Without batting an eyelid or even thinking, he answers the question of whether he has observed land theft: “Of course! There are lands that Jews used. Nobody came for years and objected.”

“And then there is private property of Arabs that lies within a settlement virtually enclosed by the settlement. However, if it is proven that a Jew is sitting on land belonging to an Arab, he will be expelled from there by an Israeli court. The Israeli legal situation is clear: Anyone who does not demonstrably sit on his own land must be removed from there.”

Biblical law

“Incidentally, this is also in accordance with biblical law”, the Orthodox Jew with the yarmulke on his head explains. In his remarks current politics and old biblical stories involuntarily merge into each other.

“The fact that Israelites were promised the land by God does not mean that they could simply take whatever they want. Abraham, our father, had to acquire the Cave of Machpelah in Hebron at the full market price, as did Jacob his field in Shekhem or King David the Temple Mount in Jerusalem.” The law of the Bible, which prohibits any land theft, still applies from the point of view of these Torah-believing Jews.

Jews against Jews

And then Yossi also knows of cases in which Jews stole land from other Jews: “Here, for example, in the settlement of Othniel, a Jew bought land. Now other Israelis are challenging this land purchase in court.”

Again, not much has changed since Biblical times, if you consider the story of the Israelite Nabot. The Israelite King Ahab had simply taken his vineyard from him to grow cabbage there.

Palestinians against Israelis

Even in the land dispute between Palestinians and Israelis, not everything went according to the law. Yossi Edri makes no secret of that.

In 1929, the Jewish community in Hebron, which had existed for more than three thousand years, had been wiped out by a pogrom. In the following years, Arabs had settled in the abandoned Jewish houses.

In the early 1980s, Yossi was involved with other young Israelis in locating the “inheritance of their fathers” in order to win them back. A Jewish woman who had married an Arab and returned from Jordan supported their efforts.

“Redemption” of old Jewish property

If it was clear that some real estate was originally Jewish property, “we had to convince the residents to leave the houses.” The government provided compensation for such cases and “we helped them find new accommodation.”

But when financial incentives were not enough, there were also “hints”, threats were made – “and every now and then a hand grenade was thrown into a garden.” Yossi remembers actions that were in no way supported by the Israeli government. He himself describes them today as “illegal” and “criminal”.

Even property that has been demonstrably stolen from Jews should not simply be taken back by force. You must buy it out. In Hebrew, Yossi Edri talking about these issues uses an old, Bible-based term, which is usually translated as “redeem”.

Western stereotypes

To the cliché reproach that the immigrating Jews had simply robbed the Palestinian natives of their land Edri answers with vehemence: “Every soil on which we settle must be bought – exactly like Abraham bought the Cave of Machpelah.”

“Yes, God has promised us this land. Yes, we have returned – but then we bought all the land on which we live today, from the estates in the beginning of the 20th century until today. We did not drive anyone out!”

Purchase offers

The conversation in the off-road vehicle on the way, as well as in the office or at home with the obligatory cup of black tea, is constantly interrupted by telephone calls. Not only security personnel or military people are reporting, wanting to answer questions or seeking solutions. Many of Yossi’s calls are made in Arabic.

For a considerable number of Palestinians, the settler security chief with the Oriental mentality and unmistakable sympathy for this rugged country and its battered people is a last resort in a politically and economically melded situation.

Be it family or tribal disputes, problems with the Palestinian Authority (PA) or simply economic emergencies. Again, and again, Palestinians see no other way out than to turn to their immediate Jewish neighbors.

Legal uncertainty in the PA

“There is no legal security in the PA,” Edri knows. He tells about a man whom the Palestinian security services hung on his hands for 70 days. Yossi laughs bitterly: “They have learned well from us. Not only Arabs do that. Such things have also been done by Jews. That’s the terrible reality.”

He continues leafing through documents and points to one sheet: “That’s confidential. If it becomes known that we know about it, this guy will spend the rest of his life in jail, if he survives at all…”

“There a father did stupid things and pulled his sons into it… They broke both his hands… There the utmost caution is to be exercised, otherwise he will get shot – and I had such cases…”

Land sale with deadly consequences

Again and again it is about selling land to Jews. This reproach is obviously also raised occasionally within Palestinian society to put pressure on someone. Someone who is accused of land sale to Jews will most certainly pay with his life.

“The economic situation among the Arabs around here is sometimes so bad that people do not have enough to eat,” Yossi explains: “That’s why people offer me their land for sale.”

From hundreds of conversations he knows: “Many Palestinians want to leave here. They just need money to be able to leave. The Palestinian Authority is afraid of this movement. They set up a special unit to combat this phenomenon.”

“But people see that the PA is a dictatorship. In Israel and Europe, they see democracy. And that is exactly what they want,” this Moroccan Jew expresses his Arab neighbors years before Europe was flooded by a flood of disappointed Muslims.

The consequences of the BDS movement

While the Jewish land buyer continues to inform me on how he finds his clients, I have in front of my eyes the direct impact of the “Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions” (BDS) movement. Through economic pressure Western non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and especially churches try to force the Jewish state to bow to their political agenda.

The result: The Jewish settlers move their businesses a few miles farther west into the heartland of the State of Israel. They dismiss their Palestinian workers.

Consequently, the Arabs are being forced to sell their land to Israelis. Otherwise, they see no way to meet their daily needs. Thus, Western efforts to undermine Israel’s settlement policy are forcing Palestinians to sell their land to Israelis.

Footnotes:

[1] From the Arabic “Mal”, which means “money” or “silver”.