Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

The man whom Psalm 1 praises as blessed (v. 1) has “pleasure in the Torah” (v. 2a). The question as to how this “lust for the law” expresses itself in a practical way is answered in the second part of verse 2:

“He murmurs in His torah day and night.” – Martin Luther had a great love for the word of God. He wrote about Psalms 1:2: “I cannot adequately emphasize the power and loveliness of this word, because this meditatio consists in the first place of paying close attention to the words of the law, then also of holding different scriptures against each other. This is a kind of lovely hunting, yes, a skipping of deer in the forest mountains, where the Lord arouses the hinds and bares the woods (Psalms 29:9).”[1]

Surely, our text describes a man “who is searching and thinking”.[2] The word, which many German translations of the Bible[3] refer to as “muse”, definitely describes a “constant and most intensive thinking”.[4] The Hebrew root “הגה/hagah”, which we translate here as “murmuring” or “mumbling”, however, includes much more. “Thinking,” no matter how intense, “Meditatio”[5], no matter how wildly playful, are neither to be seen nor heard. In which thoughts a person is lost, an outside observer can at most guess.

The “הגה/hagah”, in contrast, is visible and audible. In Isaiah 31:4, it is a lion that growls or purrs – depending on whether the giant cat enjoys its prey or means to defend it. In Isaiah 38:14, “הגה/hagah” describes the cooing of a dove. “Therefore St. Augustine has in his translation ‘to twitter’ (garrire) in a beautiful figurative language (metaphora), because the twittering (garritus) is an exercise for birds just as for man (whose special gift [officium] is speaking) that talking about the law of the Lord should be an occupation.”[6]

Growling, purring, cooing, twittering, mumbling

Joshua is requested: “The scroll of this Torah should not depart from your mouth. Murmur it day and night” (Joshua 1:8). David confesses: “My tongue mumbles your righteousness” (Psalms 35:28). In both cases more is meant than quiet meditation or invisible thinking.

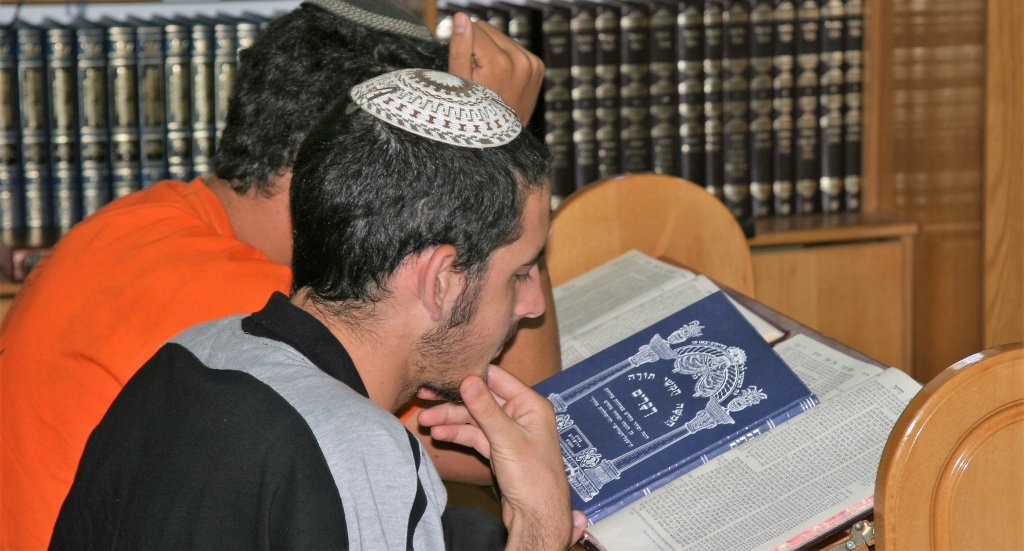

The Hebrew word “הגה/hagah” describes “that active thinking”, better still a “thoughtful expressing of human speech”.[7] Looking at the one who is in love with Torah, it cannot be overlooked how he constantly moves in his mouth what keeps his mind busy. “It is the way and the kind (natura) of all lovers, that they like to chat, sing, dance, strive, joke about, and wish to hear of what they love. Therefore, this lover, the blessed man, has his beloved object, the law of the Lord, constantly in his mouth, always in his heart, permanently (if it can be) in his ears.”[8]

That may sound like a growling, purring, cooing, twittering, chirping, muttering, mumbling or murmuring. In any case, it reflects an occupation that can be objectively perceived by outsiders.

Thinking visibly

The Malbim[9] describes the “הגיון/higayon” (= the “murmuring,” in modern Hebrew also the “logic”) as “intermediate between talking and thinking”.

“It is the very specific expression denoting the thoughtful ‘study’ of the Torah, which is essentially not accomplished through mere thoughts without words” – Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch[10] described the Jewish way of dealing with the Word of God – “but, instead, requires even from him who ‘studies’ alone the precise verbal expression of the thought which is being brought to life.”[11]

I remember vividly how, at the very beginning of our time here in Israel, a rabbi friend of mine interrupted me when I spoke of “reading the Bible”: “The Bible is not being read,” he corrected me briskly, “the Torah must be learned!” And the learner seeks to understand and reads aloud. He lets his voice be heard and repeats it many times.[12]

The English preacher king Charles Haddon Spurgeon wrote about Psalms 1:2: “He takes a text and carries it with him all day long; and in the night-watches, when sleep forsakes his eyelids, he museth upon the Word of God.” Thus, the word of God becomes established in him. He learns it by heart so that it becomes his constant companion. “The law of the Lord” is the daily bread of the true believer.[13]

Exciting, invigorating, refreshing, attractive

The “logical mumbling of my heart before you” (וְהֶגְיֹ֣ון לִבִּ֣י לְפָנֶ֑יךָ) is the climax of Psalm 19. Therefore, it is appropriate at this point to recall what David says in the second half of Psalm 19 about the Word of God: “The Torah of the Lord is perfect, it restores life. The testimony of the Lord is trustworthy, it makes the simple wise. The Lord’s commands are straightforward, they please the heart. The commandment of the Lord is clear, it enlightens the eyes. The fear of the Lord is pure, it stands forever. The judgments of the Lord are truth, as an entirety they are right. They are more pleasant than gold and lots of fine gold. They are sweeter than honey and natural nectar.”

Those who murmur the law of the Lord are not concerned with something boring, outdated, dusty or oppressive. Rather, the Torah of the Heavenly Father is not only reliable and trustworthy, but even exciting, invigorating, refreshing, attractive.

“Day and night”

Rabbi Hirsch saw, like many Jewish teachers, that Torah learning should not be just an occupation of the experts, but something that shapes the whole nation of Israel. It is inseparable from the character of the Jewish people. Therefore, the tension between daily life and Torah study is the norm, not the exception. Hirsch comments on Psalms 1:2: “During the day, the time of his active fulfillment of life’s tasks, the Torah is the guide for his thinking, his desires and his actions… the night, when man rests from his daily labors and turns to his perceptive and sensitive inner being, is devoted to the Torah, to ‘study’.”[14] Martin Luther opined: “The righteous loves the law of the Lord and bears it in mind, even when he sleeps.”[15]

The Mishnah, the centerpiece of the Talmud, transmits a saying of Shammai the Elder, a contemporary of Jesus: “Make your Torah keva” (Avoth 1:15). “קבע/keva” is something “solid,” “lasting,” “permanent.”

Modern Orthodox Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein (1933-2015), former head of the Yeshivat Har Etzion, a Talmud school south of Bethlehem, interpreted this “קבע/keva” in several ways: First, make the Torah something permanent that shapes your entire day.[16] Lichtenstein was aware that many people do not have a choice. They must make a living. “But when he comes home, he can decide whether to read the paper and watch television or whether to sit down and to learn. Here the question of what is primary and what is secondary comes to the fore”,[17] the Israeli rabbi explained.

Secondly, Lichtenstein saw the “lasting” (קבע/keva) as something “essential,” “permanent” in daily life, as “indispensable.” Adherence to Torah ought to be “not negotiable”.[18] And third, the Torah, as something “enduring.” It should be so “ingrained and absorbed, that it becomes part of you.”[19]

From the “Torah of the Lord” to “his Torah”

Without quoting Psalm 1 in his speech, Rabbi Lichtenstein refers in these statements to an observation of the traditional Jewish exegetes of Scripture.[20] Jewish exegetical tradition repeatedly observes multiple meanings in the Hebrew wording of Scripture.

Here in the beginning of Psalm 1:2 it is the “Torah of the Lord” that the blessed one finds his pleasure in. In the second part of the verse, after he has labored in it, after establishing his learning and internalizing the word, it is called “his Torah.” By “murmuring in the Torah,” the “Torah of the Lord” progressively becomes the Torah of that man, who is called “blessed” at the beginning of our text. “The general law, originally given for all, becomes his very own personal law.”[21]

Practically “relying on the Lord”

Where Jeremiah 17:7 stated in a general and theoretical manner that the blessed one “relies on the Lord” (אֲשֶׁ֥ר יִבְטַ֖ח בַּֽיהוָ֑ה) and seeks “the Lord as his refuge” (וְהָיָ֥ה יְהוָ֖ה מִבְטַחֹֽו), the parallel in Psalm 1 shows, how this may be demonstrated practically in daily life. “Relying on the Lord” and “seeking one’s safety in the Lord” becomes visible in the personal priorities of a human being. Those who give a high priority to God will certainly also find time to engage with the Word of God. Just as a car lover talks about vehicles day and night, reserving every spare minute for his hobby, a Torah lover will “twitter his Torah day and night.”

In his farewell speech to the people of Israel, Moses presented his audience with a choice between blessing and curse (Deuteronomy 28). He promised to the “blessed one” (Jeremiah 17:7) and the “happy one” (Psalms 1:1) that God would make him the “head and not the tail” (Deuteronomy 28:13). The disobedient and “cursed one”, on the other hand, is threatened by the existence as a tail (Deuteronomy 28:44). It is worth reading the context of Deuteronomy 28 to understand what the author of Psalm 1, like the author of Jeremiah 17, alludes to.

Looking at how much time we dedicate to God’s Torah in our lives, shows whether we are “head” or “tail.” Whether we consciously decide what shapes our lives, thinking and consequently our actions – or whether we spinelessly follow our natural impulses, the pressures of daily life, the circumstances of our time or even the twittering of our smartphones, like a tail follows his dog.

People who could call themselves neither “blessed” nor “happy,” but rather stressed, hunted, or even burned out, quite often have a hierarchy of priorities that does not fit the objective which the Creator intended for us.

“Kingdom of God” first

Here in Psalm 1 we have before us a man who seeks first the kingdom of the one, true, living God and strives for His righteousness (Matthew 6:33). Through the “murmuring of the Torah day and night,” over time, the “treasure” that Jesus mentioned several times develops (Matthew 12:35, 13:52). This “treasure” is crucial to what a person is and what he may give to his fellow men. The value we practically attach to the Word of God in our daily lives determines how we influence our environment.

Martin Luther was interested in bringing the word of God to the people. That’s why he translated the Bible into German. Therefore, he summarized the essence of the Christian faith in catechisms. Therefore, he was also aware that the practical implementation of what Psalm 1 shows is fraught with difficulties.

Luther wrote: “Do not believe that the impossible is required of you; just try it, and I know that you will be happy and grateful. First, practice with one psalm, even a single verse of a psalm. You have achieved enough, if you have learned in a day or even a week to make one verse in your heart alive and strong (spirantem). After this beginning, everything will follow, and you will come to an exceedingly rich treasure of knowledge and affection (affectionum); just be sure that you do not let yourself be frightened by over-indulgence and desperation.”[22]

Psalms 1:2 challenges us to develop a lifestyle shaped by the Word of God. Only if we succeed personally on a small scale will we be able to experience the radiation of “happiness” and “contentment,” i.e., the “shalom” of God, “higher than all reason” (Philippians 4:7) into our society. And that is exactly what a world needs in which the “Gentiles rage” (compare Psalm 2).

Footnotes:

[1] Johann Georg Walch (hg.), Dr. Martin Luthers Sämtliche Schriften. Vierter Band. Auslegung des Alten Testaments (Fortsetzung). Auslegung über die Psalmen (Groß Oesingen: Verlag der Lutherischen Buchhandlung Heinrich Harms, 2. Auflage, 1880-1910), 233.

[2] C.F. Keil and F. Delitzsch, Psalms 1-35, Commentary on the Old Testament vol.5/1. Translated by Francis Bolton (Peabody, Massachusetts/USA: Hendrickson Publishers, February 1989), 85.

[3] Luther, Elberfelder, Menge.

[4] Samson Raphael Hirsch, The Psalms, rendered into English by Gertrude Hirschler (Jerusalem/New York: The Samson Raphael Hirsch Publication Society. Feldheim Publishers, New Corrected Edition 1997), 3.

[5] English translations render “meditate” (King James, NIV, ESV).

[6] Johann Georg Walch (hg.), Dr. Martin Luthers Sämtliche Schriften. Vierter Band. Auslegung des Alten Testaments (Fortsetzung). Auslegung über die Psalmen (Groß Oesingen: Verlag der Lutherischen Buchhandlung Heinrich Harms, 2. Auflage, 1880-1910), 232-233.

[7] Samson Raphael Hirsch, The Psalms, rendered into English by Gertrude Hirschler (Jerusalem/New York: The Samson Raphael Hirsch Publication Society. Feldheim Publishers, New Corrected Edition 1997), 4.

[8] Johann Georg Walch (hg.), Dr. Martin Luthers Sämtliche Schriften. Vierter Band. Auslegung des Alten Testaments (Fortsetzung). Auslegung über die Psalmen (Groß Oesingen: Verlag der Lutherischen Buchhandlung Heinrich Harms, 2. Auflage, 1880-1910), 235.

[9] Meir Leibush Ben Yechiel Michael Weiser (1809-1879), known by the acronym “Malbim”, was born in Volochysk, which today is part of Ukraine, and worked in Eastern Europe as a rabbi, Talmudist, Bible exegete, and preacher. During his time in Kempen, Posen, (1845-1859) he was nicknamed “Kempner Maggid”. As an inexorable opponent of the reform movement and the Jewish Enlightenment, the Malbim came into conflict with both Jewish and non-Jewish authorities, was slandered, arrested and expelled as a political insurgent. He officiated as chief rabbi of Romania and Königsberg. His biblical interpretation focuses on the “depth of language” and the “basic meaning of the text” “based on precise linguistic rules”. The Malbim assumed that there are no repetitions in Scripture, but that every (apparent) repetition always reveals a new aspect of content. In addition, in his preface to the interpretation of the Prophet Isaiah interpretation, he emphasizes that a prophet does not pass on his own thoughts, but words “put into his mouth and pen by the Spirit of the Lord who was upon him.”

[10] Samson Raphael Hirsch (1808-1888) came from Hamburg and served as Chief Rabbi in Oldenburg, Aurich, Osnabrück, Moravia and Austrian Silesia. As a distinguished representative of Orthodoxy, he was an outspoken opponent of reformist and conservative Judaism. Hirsch attached great importance to the study of all Scripture. From 1851 he was rabbi of the separatist Orthodox „Israelitischen Religions-Gesellschaft“ (“Israelite Religious Society”), engaged in education and published the monthly magazine “Jeschurun”. Hirsch had a great love for the land of Israel, was at the same time, however, an opponent of the proto-Zionist activities of Zvi Hirsch Kalischer. He is seen as one of the founding fathers of the neo-orthodox movement.

[11] Samson Raphael Hirsch, The Psalms, rendered into English by Gertrude Hirschler (Jerusalem/New York: The Samson Raphael Hirsch Publication Society. Feldheim Publishers, New Corrected Edition 1997), 4.

[12] עמוס חכם, ספר תהלים, ספרים א-ב, מזמורים א-עב (ירושלים: הוצאת מוסד הרב קוק, הדפסה שביעית תש”ן/1990), ד.

[13] Charles Haddon Spurgeon, Die Schatzkammer Davids. Eine Auslegung der Psalmen von C. H. Spurgeon. In Verbindung mit mehreren Theologen deutsch bearbeitet von James Millard. I. Band (Wuppertal und Kassel/Bielefeld: Oncken Verlag/Christliche Literatur-Verbreitung, 1996), 5. The Treasury of David by Charles H. Spurgeon, Psalm 1: http://archive.spurgeon.org/treasury/ps001.php (03.02.2019).

[14] Samson Raphael Hirsch, The Psalms, rendered into English by Gertrude Hirschler (Jerusalem/New York: The Samson Raphael Hirsch Publication Society. Feldheim Publishers, New Corrected Edition 1997), 3-4.

[15] Johann Georg Walch (hg.), Dr. Martin Luthers Sämtliche Schriften. Vierter Band. Auslegung des Alten Testaments (Fortsetzung). Auslegung über die Psalmen (Groß Oesingen: Verlag der Lutherischen Buchhandlung Heinrich Harms, 2. Auflage, 1880-1910), 234.

[16] Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein, “By His Light. Character and Values in the Service of God,” adapted by Rabbi Reuven Ziegler (Yeshivat Har Etzion: Maggid Books, 2016), 55.

[17] Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein, “By His Light. Character and Values in the Service of God,” adapted by Rabbi Reuven Ziegler (Yeshivat Har Etzion: Maggid Books, 2016), 57.

[18] Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein, “By His Light. Character and Values in the Service of God,” adapted by Rabbi Reuven Ziegler (Yeshivat Har Etzion: Maggid Books, 2016), 59.

[19] Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein, “By His Light. Character and Values in the Service of God,” adapted by Rabbi Reuven Ziegler (Yeshivat Har Etzion: Maggid Books, 2016), 60.

[20] Rashi, Radak, Malbim referring to the Babylonian Talmud, tractate Avodah Zarah 19a.

[21] Samson Raphael Hirsch, Psalmen (Basel: Verlag Morascha, 2. Neubearbeitete Auflage 2005), 3.

[22] Johann Georg Walch (hg.), Dr. Martin Luthers Sämtliche Schriften. Vierter Band. Auslegung des Alten Testaments (Fortsetzung). Auslegung über die Psalmen (Groß Oesingen: Verlag der Lutherischen Buchhandlung Heinrich Harms, 2. Auflage, 1880-1910), 252.