Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

On October 31, 1517 Martin Luther sent his “Disputatio pro declaratione virtutis indulgentiarum” to Albrecht von Brandenburg. The archbishop of Mainz and Magdeburg never responded. Therefore, Luther began by himself to circulate his so-called “95 Theses” in which he denounced the commercial abuse of the indulgence trade. In the first German print editions, the treatise appeared under the title “Propositiones wider das Ablas” (“Theses Against the Indulgence”). Whether the reformer ever personally nailed his letter to the Schlosskirche of Wittenberg, is controversial among historians.

Man is saved “sola gratia”

Luther’s resistance to the practice of indulgence sprang from the realization that a person cannot earn his salvation from his own efforts. Eternal bliss is not for sale. Man is reconciled to God “by grace alone” – “sola gratia” in Latin – and thus saved.

Martin Luther as a monk had endeavored to come to grips for himself and ultimately for the whole of Europe with his own past, the religious practices of his time and the panic that was so rampant in the Middle Ages facing graphic descriptions of hell. Originally his antipode had not been another religion, neither “Jews” nor “Turks”, but rather his own Catholic church.

Jewish justification by works versus the Christian message of grace

How come that for Luther’s spiritual heirs up to this very day view “Judaism” with its justification by works so often in sharp and irreconcilable contrast to “Christianity” as the religion of grace? Christians seem happy to leave “the law” and its obligations to the Jewish people, while claiming for themselves “the gospel” of God’s unconditional love to us. “The letter kills, whereas the Spirit brings to life” (2 Corinthians 3:6) can often be heard – if not expressed verbally, then in between the lines – as typical description of the antipode of Judaism versus Christianity.

As a textual witness, Paul’s letter to the Galatians is cited. It is overlooked, however, that the apostle had not written his letter against Jews who perceived themselves in a commitment to God’s Torah. Rather, Paul denounced an abuse of Judaism, which was practiced in Galatia. His Letter to Galatians is not addressed to Jews, but to non-Jews; and not to people who reject Jesus as Messiah, but to the Jesus-believing, “called out” congregations “in Galatia” (Galatians 1:2), whose efforts to achieve a more prominent position before God by performing certain practices and Judaizing Paul criticized. Paul himself as member of the Jewish people and faith offered sacrifices on his last visit to the temple in Jerusalem (Acts 21:26) – certainly not in order to assure himself of his own status before God and salvation by performing Jewish religious rites.

Not at all inconvenient to Jews

Somehow, the distinction between Christianity which is saved “by grace alone” and Judaism, which has to fulfill its commandments, seems to be not all inopportune to some of our Jewish contemporaries. After all, this ensures a clearly defined, unambiguous, dogmatically not so easily surmountable distance.

Dashingly-casual and without too many preliminary considerations a dear orthodox-Jewish friend once banged my head: “You Christians may push Jews into the gas chambers during the day and sing your Christmas songs in the evening. You are saved by grace alone. We Jews, in contrast, have to put into practice in everyday life what we believe!”

Such verbal slip-ups are very valuable from my point of view. They reveal what we really think of each other – long before our words and thoughts were diplomatically refined and thus declared useful in Jewish-Christian dialogue. Because of the late evening hour and perhaps also because of my own background, I was not able to respond to my learned rabbinical friend at the time, than letting him know: “It is not that easy with us either.”

An original Jewish principle

Sometime after that evening I attended a lecture another Rabbi gave in Jerusalem in Hebrew to Jewish listeners. At some point he stated: “Christians assume that they have discovered that a human being can be saved by grace alone through faith. Originally, however, this is a ‘primal Jewish’ principle.”

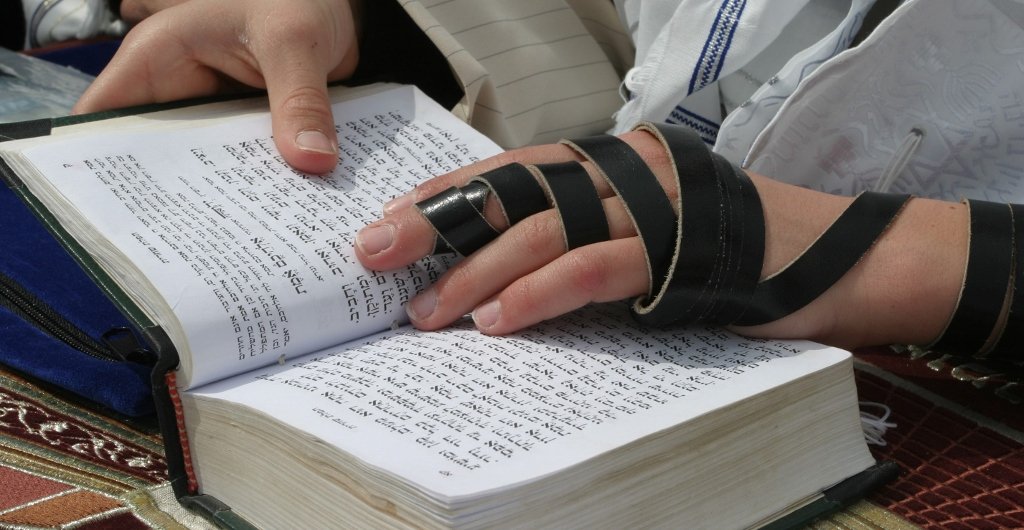

In the same breath, this speaker provided a key for my further reflection, in pointing out: “If there is a dogmatic that the majority of faithful Judaism is committed to today, that is the siddur, the Jewish prayer book.”

The siddur as dogmatic of Judaism

As a result, I sat down and worked through the entire Jewish prayer book, in this case a Sephardic edition, in search of justification by works. In fact, I found something.

At one point, the Jewish prayers come very close to the basic idea of the medieval indulgence trade, which Martin Luther fought so vehemently. The Dominican monk Johann Tetzel, one of Luther’s major adversaries, had formulated: “As soon as the money in the box sounds, the soul jumps out of purgatory.” The idea was to pay some amount of money in this world so that a beloved person in the afterlife will be better off. Tetzel raised thus quite some funds for the construction of St Peter’s Dome in Rome.

Alms for the salvation of the deceased

In the prayers for the deceased, which are spoken after the reading of the Torah on the last day of the Passover, the Feast of the Weeks, on Yom Kippur and at the conclusion of the Feast of Tabernacles at Shmini Atzeret, the believer recites: “Remember, oh God, the soul of the deceased, for which I give alms. As a reward, his soul may be counted among the living, together with the souls of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, Sarah, Rebekah, Rachel and Leah, and the remnant of the righteous men and women in the Garden of Eden.”

Admittedly, these prayers are among the very few passages in the siddur that were not taken directly from the Hebrew Scriptures. But at least: Here we have the Jewish counterpart to the indulgence trade of the catholic church of the Middle Ages.

He who sanctifies us in his commandments

And: Is there not myriad of Jewish blessings which are initiated with the words: “Blessed are you, Lord, our God, King of the universe, who sanctifies us by his commandments”? Is that not justification by works when you remind God that – admittedly: He! – but after all I myself will be sanctified by keeping His commandments?!

Jesus-believing Jews do not like this initiation of Jewish blessings, and change them in different ways, or bypass them. Where I myself have made these blessings my own prayer, I have often replaced the “asher kideshanu bemitzvotav” (“who sanctified us in His commandments”) by “asher kideshanu beMeshicho” (“who sanctifies us in His Messiah”) – which has firmly established itself in our own personal family tradition on Shabbat eve. By confessing that it is the Messiah – as opposed to keeping the commandments! – who sanctifies us, I felt safely back on solid Orthodox Christian grounds.

The incarnate Word of God

But, is not Jesus, according to the New Testament, the Word of God made flesh (John 1:14)? And this word will only be fully understood, becomes comprehensible and is implemented in daily life by practically fulfilling the commandments.

Does not Yeshua Himself in His famous prayer for those who will follow His teachings bring up the idea that His disciples will be sanctified by the commandments asking His father: “Sanctify them in the truth. Your word is truth” (John 17:17)?

Furthermore, he had previously promised His disciples: “You are already pure – that is, ‘sanctified’! – through the word that I have spoken to you” (John 15:3). He explains the commandment “remain in Me”, that is, “in Messiah” (John 15:4) a few sentences later on by paralleling the “if you remain in me” with the statement “and my words remain in you” (John 15:7).

Is it then not “His commandments” through whom He(!) “sanctifies me” if we try to sum all this up for concrete day-to-day life, simply and unmistakably, without any theological embellishment?

The needle in the haystack

It must be admitted: With the prayers for the deceased and the attempt to understand “asher kideshanu bemitzvotav” as dogma of merit, I held up the desperately searched needle in the proverbial haystack.

A comprehensive study of the Jewish prayer book draws a very different picture: The siddur breathes the “reformatory sola gratia” on each page and thus shapes Jewish life thoroughly. For reasons of time and space, only a few examples are mentioned here.

The siddur breathes the “sola gratia”

Every believing Jew begins daily with the morning prayer, in which he confesses each time: “Ruler of all worlds, Lord of Lords, not in our own righteousness, we base our pleading before You, but upon Your great mercy. What are we? What is our life? What is our appearance? What our righteousness? What is our salvation? What our power? What our strength? What shall we say before You, Lord, our God, God of our fathers? Are not all the most capable human beings like nothing before You? Are not the most famous people as if they had never existed? The wise without knowledge? The educated without reason? The greatness of their achievement is nothing but chaos. The days of their life is nothing but a whiff before You.”

When it comes to the redemptive act of God par excellence, the gathering of the people of Israel into the land of Israel, Jewish worshiper do not refer to the merits, the faithfulness or the privileges of His people acquired through their suffering, rather they plead again in the ‘shaharit’ (the morning prayer): “Gather the dispersed ones of those who hope for You from the four corners of the earth. All who come into the world shall acknowledge and know, that You alone are the [one, true, living] God, the Most High for all the kingdoms of the earth.”

Not achievements, but God’s honor decides

Not achievements or merits of believers are mentioned in these prayers as reason and motivation for God’s redemptive actions, but the honor of the living God and His purpose in view of the whole gentile world: “May the Lord be king over the whole earth. In that day the Lord is One and His name One.”

Over and again, the character of God is appealed to: “He is merciful, He covers misdemeanor, and does not destroy.” For “You are the first. You are the last. Except You we have no king, savior and redeemer.”

“The Thirteen”

Everything focuses on “the Thirteen” – the thirteen attributes of the God of Israel: “Lord, Lord, God, compassionate and merciful, patient and of great mercy and faithfulness; who shapes grace for thousands; who bears sin, crime and misconduct; who purifies and forgives our sin and misdemeanor and assigns us an inheritance” (Exodus 34:6-7).

From the consciousness of these fundamental traits of the Creator follows logically the invitation to the faithful: “Do not seek your security from highly respected and powerful people, from human beings, because there is no salvation with them… Blessed is he whose help is the mighty God of Jacob!”

This realization then leads repeatedly – almost automatically – to the quest: “Deliver us with complete salvation, soon, for the sake of Your name, because You are a mighty redeemer. Blessed are You, Lord, redeemer of Israel.” “Let the offspring of David, Your servant, soon sprout, and raise His horn in Your salvation, because in Your salvation we have built our hope all day long. Blessed are You Lord, who makes the horn of salvation sprout.”

Judaism as religion of grace

The prayers of Israel prove Judaism as a religion of grace. This insight should not be surprising. Like no other prayer book, the siddur is anchored in the Holy Scriptures. There from the very beginning salvation is recorded as an act of grace of the Creator God. “You have redeemed us from Egypt, oh Lord our Lord, from the house of slavery You have freed us…”, remembers the Jewish worshiper. Israel’s exodus from Egypt, the land of death and enslavement, was at its source the Creator’s idea and in its execution the work of Him who opposed the Egyptian Pharaoh as the Father who is zealous for His firstborn son.

Eucharist and Seder meal

From the historical roots, the Christian church celebrates – whether she is aware of it or not – in the Eucharist together with the Jewish people the Passover meal. In the Lord’s Supper, the church remembers, teaches and visualizes the saving action of God. In the holy communion, the Body of Jesus gathers to celebrate the redemption of the people of God – certainly with the additional instruction of the Messiah: “From now on, do this in remembrance of Me!” (Luke 22:19).

Even for Christians from the gentile nations, it is only after the exodus from the power of the pyramid-like overwhelming tombs and from the bondage in separation from God that we arrive at Mt Sinai, where God reveals His will. There, at Horeb, the Creator tells us, what He would like us to do, gives His children direction, sets a goal for them, entrusts His people with the Torah. This is not just true in the history of the nation of Israel. This is true for the path of faith of every child of God, may he or she be a Jew or a non-Jew.

From the Reed Sea to Mt Sinai

And when God reveals His will, it is always a call to obedience, connected with the expectation of a life in faith, the commitment to a corresponding lifestyle. In this, the gentile world does not differ from Israel. An assumed relationship with God that is not reflected in daily life is nothing but a philosophical pull-up. Faith that does not flow into action is dead (James 2:17,26). This applies to Christians as well as to Jews.

Messiah Yeshua had not only told his successor that he had not come “to dissolve the Torah or the prophets.” He had also assured them: “Until the heavens and the earth pass, neither a yota nor a dot of the Torah will fade until everything is being accomplished.” And finally, in this context, he even warned his listeners: “If your righteousness does not surpass the righteousness of the scribes and Pharisees, you will not enter the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 4:17-20).

Without alternative “sola gratia”

The God of Abraham, Isaac and Israel saves people “by grace alone”. This may have been an absolutely new discovery for the Augustinian monk Martin Luther. In the late Middle Ages of Central Europe, which was shaped by the thought of the catholic church at the time and the highly fashionable endeavor to build a splendid St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, it may have been unheard of.

Certainly, there have been and still may be Jewish people who believe that by fulfilling commandments, observing certain rites and their own religiously-motivated accomplishments, they may gain respect, wealth, health and perhaps even redemption in the sight of God. This phenomenon is simply human and part of every religion – incidentally also of Christianity.

However, for the biblical revelation as we see it in the so-called Old and New Testament, it was clear from the very beginning that a single human being, like humanity in general, may be redeemed from the curse of sin, disease, injustice, war, suffering and death exclusively by the loving and undeserved devotion of the Creator towards His creatures. The only thing that a person may contribute to the redemptive process is to acknowledge the Creator as Lord, Savior and Father – and, thus, to call upon His name (Romans 10:13 with reference to Joel 3:5). In this point, Jews and Christians should agree.