Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

On the political stage of the Middle East, I have never seen anyone ask about the biblical borders of the Promised Land. I know of no politician who pursues an agenda of translating prophecies of the Bible concerning the borders into political reality.

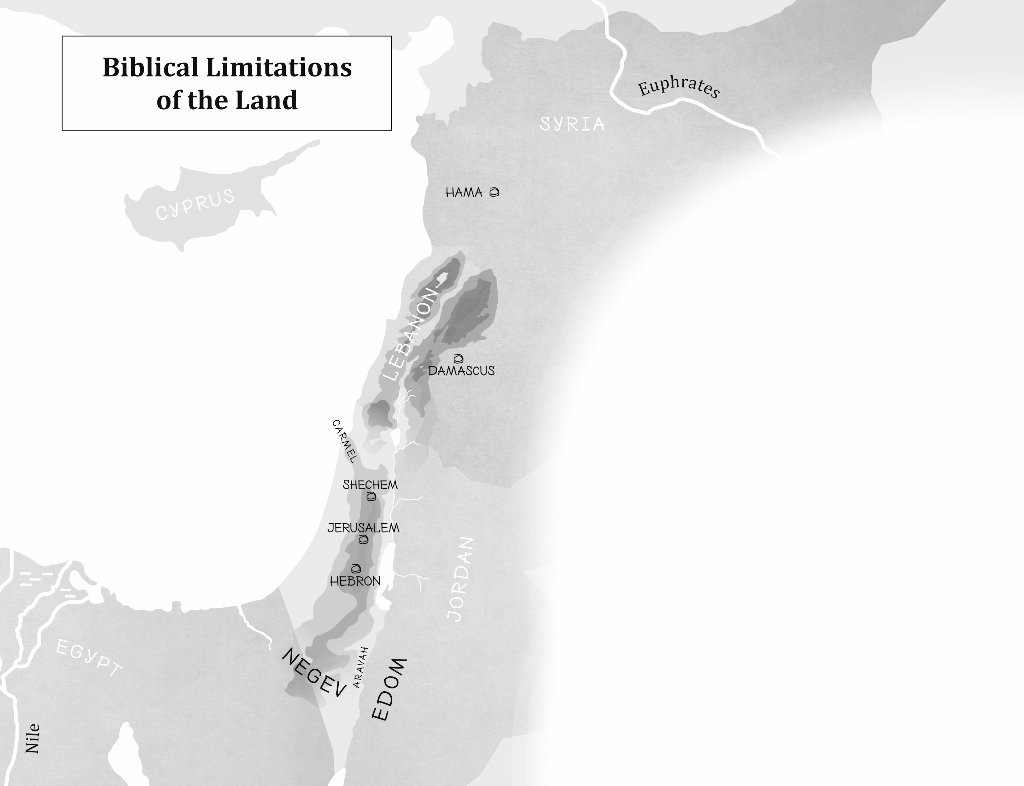

However, I come across Christians with the question of when the state of Israel will reach its biblical borders. And in past years, secular journalists and political analysts have given publically thought to whether certain Israeli politicians dreamed of a “Greater Israel within biblical borders”. It is therefore appropriate to outline what the Bible actually says about the borders of the Promised Land.

The land is limited

First of all it should be noted, that the land to which the Hebrew people were led by Moses was never borderless. It always had its limits.[1] Egypt, in the southwest of the land of Canaan, is as obviously a foreign country from a biblical perspective,[2] as was Assyria in the northeast.[3] The fact that the Promised Land is limited may also be recognized by the acknowledgement that it can become too small.[4]

Consequently, the immigrating people of God may not simply take whatever they like when they think they are capable of it. The Bible does not support international law based on majority decisions, nor does it accept as rightful owner whoever prevailed in a conflict as the more successful.

The creator sets borderlines

According to the Bible, it is the one, true, living God who distinguishes between language groups and ethnic entities (Genesis 11:9), causes nations to migrate (Amos 9:7) and set the limits of the peoples.[5]

A crucial factor in this is people‘s obedience to the Word of God. Therefore, from a biblical point of view, the borders God sets for a nation are never an unchangeable “Law of the Medes and Persians” carved in stone.[6] The borders of a country depend on the relationship of the respective people with the living God. Their course may therefore indicate something about this relationship.[7]

What belongs to the Promised Land

The Bible thinks from the center. Beginning with the story of the patriarchs up to the New Testament, it is clear that the center of the Promised Land is Zion, the city of Jerusalem. The prophet Ezekiel calls this city the “navel of the land” (Ezekiel 38:12). Jerusalem is the place that the Lord has “chosen from all the tribes of Israel.”[8]

Jerusalem is located on a mountain ridge that stretches north-south and reaches a height of over a thousand meters above sea level. In the Bible it is mentioned as “mount of the Amorite” or “Mountains of Israel.”[9] South of Jerusalem is Judea, with its capital Hebron[10]. North of Jerusalem the “Land Benjamin”[11], the “Mountains of Ephraim”[12] or later “Samaria”, with its center Shechem, present-day Nablus.[13] Mt Carmel (Jeremiah 50:19) forms an extension of this mountain range towards the northwest.

Seen from Jerusalem to the west, the mountainous region declines to the hilly country, the “shefelah” in Hebrew.[14] This is followed by the coastal plain and the natural and therefore never controversial western border of the Promised Land, the Mediterranean, also known as “Sea of the Philistines” or “the Great Sea”.[15]

To the east, the central Israeli mountains drop sharply into the Syrian-African rift valley, which is the lowest point on the earth’s surface at the Dead Sea at more than 400 meters below sea level. South of the Dead Sea, the “Aravah” separates the Negev desert in the west from the Edomite Mountains in the east and extends to the northern tip of the Red Sea, where in our time the Jordanian town of Aqaba and the Israeli resort town of Eilat are within sight of each other.

From the foot of Anti-Lebanon mountain ridge, the southern tip of which is Mt Hermon, the river Jordan flows through the Sea of Galilee from the north towards the Dead Sea, thereby forming a natural eastern border.[16] In biblical Hebrew, the Dead Sea is called “the salt sea” or “the eastern sea”.[17]

The Negev desert is a natural border at the southern end of the Promised Land,[18] which are sometimes referred to in the Bible as the “ends of the land”.[19] This borderline is flexible depending on weather conditions and technical skills of the people who live in that part of the country. In Solomon’s time Ezion Geber is mentioned,[20] a port town on the Red Sea in the area of today’s Eilat.

In the north and east, geographical and climatic conditions offer fertile cultivated land – and consequently cause for confusion, discussions, friction points and armed conflicts. Therefore, it is especially in the north and east that changes in the borders of the Promised Land due to the relationship of the people with their God are visible. The Bible alludes to these natural geographic and related climatic conditions in many instances.

The East Bank of the Jordan

Originally the areas of the tribes Edom, Moab and Ammon were foreign lands untouchable for the Hebrews. After leaving Egypt, God had explicitly told them concerning the territory of the Edomites: “I will not give you anything of their land” (Deuteronomy 2:5). The same was true of the lands of the Ammonites (Deuteronomy 2:19,37) and Moabites (Deuteronomy 2:9). Therefore, the area east of the Jordan was considered “abroad” in the book of Ruth (1:1).

However, that changed already in the time of Moses. The area “from the Arnon up to Mt Hermon”, the territories of Moab and Ammon, but then especially the “Land of Gilead”[21] and Bashan (Jeremiah 50:19), today’s Golan Heights, were added to the settlement areas of the Israelites.[22] The prophet Obadiah even foresees Israel taking possession of the “mountains of Esau” (Obadiah 19).

The expansion of the country of Israel “from Dan (at the foot of Hermon) to Beer Sheva (in the northern Negev)”is proverbial in Biblical language.[23] From the very beginning, however, Mount Lebanon,[24] the area “where you reach Hamath”[25] (today the city of Hama in Syria), and “up to the Euphrates”[26] were mentioned as northern border of the Promised Land.

The heartland is west of the Jordan

Joshua 22:9-34 reports an interesting event that is relevant in this context. The Israelite tribes of Ruben and Gad and half of the tribe of Manasseh had settled in the East Bank between “Arnon and Hermon”. Now they had built an altar near the Jordan “on the border of the territory of Israel” (verse 11). In the context of the dispute that resulted, the East Bank is strictly distinguished “from the land that belongs to the Lord, in which the Lord’s tabernacle dwells” (verse 19).

If we go back to the south west of the country, the border to Egypt is marked at “the river of Egypt”, which is the river Nile, “the Red Sea”, the “Shihor of Egypt” or “the creek of Egypt”.[27] This “brook of Egypt” is often identified with the Wadi El-Arish, which is located approximately in the middle of northern Sinai Peninsula.

In the time of the Maccabees, the extent of what is today’s modern State of Israel is described fairly precisely when 1 Maccabees 11.59 speaks “from the Tyrian ladder”, today’s Rosh HaNiqra, “to the border of Egypt”.

The subjective reference

In spite of this vast amount of border information, Scripture makes it quite difficult to establish a clearly-defined territory for the Promised Land, a clear property of the chosen people. This becomes particularly clear considering the subjective aspect that repeatedly emerges in the environment of biblical statements about the borders of the land.

We find the first border definition of the Promised Land in Genesis 13:14-15. There God tells to Abram: “Lift up your eyes. From the place where you are standing, look to the north, towards the Negev, to the east and in the direction of the sea. All the land that you see, I will give to you and your descendants.”

A panoramic view

“What you see, I will give to you!” – It remains unclear exactly where Abram stood when God made this promise, at what time of day, in what season of the year it happened, and what the weather was like. The biblical text leaves the reader in the dark about how good the eyes of the then 75-year-old were. And this despite the fact that all these would have been decisive factors in setting the borders.

With Moses, the biblical tradition is clearer. At the age of 120 years, Moses is not allowed to enter the Promised Land. As with Abraham, the drawing of boundaries is done subjectively from the perspective of the observer. However, it is clear that this is done from Mount Nebo, from one of the peaks of the mountain ridge east of the Jordan River. And it is reported of Moses that “his eyes were not weakened” (Deuteronomy 34:7).

The text also clearly states what Moses sees: From “Gilead to Dan” – that is, the whole mountain range east of the Jordan, including today‘s Golan Heights up to Mt Hermon. “All of Naphtali” – the eastern edge of the Galilean mountains. “The whole land of Ephraim and Manasseh and the land of Judah to the sea on the west” – the central Israeli mountain range with the Shefelah and the coastal plain reaching to the Mediterranean in the background. And then turning left towards the south: “The Negev”, the wilderness of Judah, the Dead Sea and right in front of Moses’ feet “Jericho, the city of palm trees” (Genesis 34:1-3).

To accept as an inheritance

The personal perspective of the one, who received the promise, his relationship with God and his relationship with the land are decisive for the drawing of boundaries in the Promised Land. This way of thinking also becomes clear when Scripture stresses dozens of times that God gives the land to the people with a mandate, namely, “to accept it as an inheritance.”[28] The Hebrew word yarash (ירש) is translated as “to inherit,” “to bequeath,” “to take as possession,” “to conquer,” “to expel,” “to settle,” depending on the context.

Connected with the land promise is thus the quite subjective task of entering, inspecting and actively taking possession of the land as an inheritance. This is why the commandment to live in the land of Israel is so important for rabbinical tradition, or, conversely, the ban on leaving the land of Israel.[29]

Stepping on the land

It was not much that God had told Abram about the land he had promised to him. Only: It is “the land that I will show you” (Genesis 12:1). Decisive for further progress was that “Abram went” (verse 4), that he arrived in the land of Canaan together with his extended family (verse 5) and passed through the land (verse 6).

After Abram had sought peace with Lot by giving him the best part of the Promised Land (Genesis 13:1-12), God repeated His purposes with regard to Abram and his descendants (verses 14-16). And then God gave Abram the command (verse 17), “Get up! Move through the land in length and breadth, for I will give it to you.”

Several generations and centuries later, Moses described the land that God intended to give to his people by announcing (Genesis 11:24), “Every place the sole of your foot will step on will be yours.” Immediately after Moses’ death, the Lord repeated this instruction to Joshua, the successor of Moses (Joshua 1:2-4): “Get up! Cross over this Jordan, you and all these people, into the land I am about to give to them, to the children of Israel. Every place the sole of your foot will step on, I have given to you as I spoke to Moses.”

In biblical thinking, stepping on the ground determines how big the Promised Land will be. Only that land which the one who received the promise will practically enter and accept as an inheritance by stepping on it is the land that God gives him. In reverse, it is true: “If you do not tread the ground, it does not belong to you.”

Thus, King Ahab took possession of Naboth’s vineyard by entering it (1 Kings 21:18-19). And “Ploni-Almoni” ceded his right to the inheritance of Elimelech to the redeemer Boaz by giving him a shoe (Ruth 4:7-8), the very “tool” that enabled him to step on the land. This way of thinking runs through the language of the entire Holy Scriptures.[30]

God has never given his people a land with borders set once for all, a plot of property that would be clearly defined in any land register – and that an “Israelite” residing in New York, Tokyo, Berlin or even Tel Aviv would be able to make work for him from a distance or even exploit it as real estate speculator.

From a biblical point of view, the size of the land and its boundaries depend on the individual’s inspection of the land and acceptance of it as an inheritance by stepping on it with the sole of his foot. Obedience to the original commission of the Creator to “cultivate and preserve the land” (Genesis 2:15) and a life in accordance with his will emerge as decisive elements considering the borders of the Promised Land.

[1] Numbers 34:2; Deuteronomy 11:24.

[2] Genesis 12:10; 15:13; 26:2-3; Exodus 5:5; 1 Kings 5:1; 2 Chronicles 9:26; Psalms 105:23; Micah 7:12; Zechariah 10:10.

[3] Micah 7:12; Zechariah 10:10.

[4] Genesis 13:6-7; 36:6-8; Isaiah 49:19-20; Zechariah 10:10.

[5] Exodus 23:31; Deuteronomy 32:8; Psalms 74:17; Isaiah 26:15; Acts 17:26.

[6] Compare Daniel 6:9,13,16 for this terminology.

[7] 1 Kings 11:33; 2 Kings 10:31-33; Isaiah 26:15.

[8] 1 Kings 11:13,32; 14:21; 2 Kings 21:7; 23:27; 2 Chronicles 6:6; 33:7.

[9] Deuteronomy 1:7; Joshua 11:16; 12:8; Jeremiah 32:44; Ezekiel 6:2,3; 19:9; 33:28; 34:13,14; 35:12; 36:1,4,8; 38:8; 39:2,4,17. The New Testament mentions “Judea, the Land of the Jews” (John 3:22; 7:1; 11:7; compare Matthew 2:19-23, where the “Land of Galilee” and the city of Nazareth are also mentioned as Jewish) and Samaria are mentioned several times in one breath (Acts 1,8; 8,1; 9,31). “Bethlehem in the land of Judea” (Matthew 2:6 quoting Micah 5:1; further compare Matthew 2:1,5; Luke 2:4) is of course important for the life of Jesus, but also today’s Ramallah is mentioned as “Arimathea, a city of the Jews” (Luke 23:51).

[10] Genesis 13:18; Numbers 13:22-24.

[11] Judges 21:21; 1 Samuel 9:16; 2 Samuel 21:14; Jeremiah 1:1; 17:26; 32:8,13,44; 37:12; Obadiah 19.

[12] Joshua 17:15; 19:50; 20:7; 21:21; 24:30,33; Judges 2:9; 3:27; 4:5; 7:24; 10:1; 17:1,8; 18:2,13; 19:1,16,18; 1 Samuel 1:1; 9:4; 14:22; 2 Samuel 20:21; 1 Kings 4:8; 12:25; 2 Kings 5:22; 1 Chronicles 6:52; 2 Chronicles 13:4; 15:8; 19:4; Jeremiah 3:19; 4:15; 31:5/6; 50:19; compare Obadiah 19; Zechariah 9:10; and further the term “Land of Ephraim” in Deuteronomy 34:2; Judges 12:15.

[13] Genesis 12:6-7; 33:18; Deuteronomy 11:29-30; Jeremiah 31:5; Obadiah 19. The story of the patriarchs further mentions Bet El and Ai, which are roughly halfway between Shechem and Jerusalem (Genesis 12:8; 13:3; 28:13-14; 35:6).

[14] Deuteronomy 1:7; Joshua 9:1; 10:40; 11:2,16; 12:8; 15:33; Judges 1:9; 1 Kings 10:27; 1 Chronicles 27:28; 2 Chronicles 1:15; 9:27; 26:10; 28:18; Jeremiah 17:26; 32:44; 33:18; Obadiah 19; Zechariah 7:7.

[15] Exodus 23:31; Numbers 34:6; Deuteronomy 1:7; 11:24; Joshua 1:3; Ezekiel 47:15,19-20; Zechariah 9:10.

[16] Numbers 34:10-12; Deuteronomy 1:7; Joshua 11:16; 12:8; Ezekiel 47:18.

[17] Numbers 34:3,12; Ezekiel 47:18; Zechariah 9:10.

[18] Genesis 12:9; 13:1; 26:6; 28:14; Deuteronomy 1:7; 11:24; Joshua 1:3; Jeremiah 32:44; Ezekiel 47:19; Obadiah 19-20.

[19] Deuteronomy 33:17; 1 Samuel 2:10; Psalms 2:8; 22:28; 59:14; 67:8; 72:8; 98:3; Proverbs 30:4; Isaiah 45:22; 52:10; Jeremiah 16:19; Micah 5:3; Zechariah 9:10.

[20] 1 Kings 9:26; 22:49; 2 Chronicles 8:17; 20:36; previously already as one station during the people’s wandering in the desert: Numbers 33:35,36; Deuteronomy 2:8.

[21] Jeremiah 50:19; Ezekiel 47:18; Obadiah 19; Zechariah 10:10.

[22] Deuteronomy 3:8-13; 4:48-49; Joshua 12:1-6; Ezekiel 47:18.

[23] Judges 20:1; 1 Samuel 3:20; 2 Samuel 3:10; 17:11; 24:2,15; 1 Kings 5:5; 1 Chronicles 21:2; 2 Chronicles 30:5.

[24] Deuteronomy 11:24; Joshua 1:3; 11:16; 12:7; 13:5-6; Zechariah 10:10.

[25] Numbers 13:21; Joshua 13:5; 1 Chronicles 13:5; 2 Chronicles 7:8; Ezekiel 47:15,20; Amos 6:14.

[26] Genesis 15:18; Exodus 23:31; Deuteronomy 1:7; 11:24; Joshua 1:3; 1 Kings 5:1; 2 Chronicles 9:26; Micah 7:12; Zechariah 9:10.

[27] Genesis 15:18; Exodus 23:31; Numbers 34:5; 1 Chronicles 13:5; 2 Chronicles 7:8; Ezekiel 47:19; Amos 6:14.

[28] Genesis 15:7; Leviticus 25:46; Numbers 33:53; Deuteronomy 3:18 and more often.

[29] See for example in the Babylonian Talmud the tractates Ketuboth 110b-111a or Baba Batra 91a; Rambam, Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Melachim U’Milchamoteihem 5:9,12. In the Hosafot to Sefer HaMitzvot (Positive Commandment 4) Ramban counts the conquest and settlement of the land of Israel as one of the 613 Commandments of the Torah.

[30] Compare the expression “not a foot wide” in Genesis 2:5 (עַ֖ד מִדְרַ֣ךְ כַּף־רָ֑גֶל) up to the words of Stephen in Acts 7:5, where the same idea is expressed with “οὐδὲ βῆμα ποδὸς.”

[…] Johannes Gerloff writes: “On the political stage of the Middle East, I have never seen anyone ask about the biblical borders of the Promised Land. I know of no politician who pursues an agenda of translating prophecies of the Bible concerning the borders into political reality. However, I come across Christians with the question of when the state of Israel will reach its biblical borders. And in past years, secular journalists and political analysts have given publically thought to whether certain Israeli politicians dreamed of a “Greater Israel within biblical borders”. It is therefore appropriate to outline what the Bible actually says about the borders of the Promised Land.” Read more.. […]

[…] Johannes Gerloff writes: “On the political stage of the Middle East, I have never seen anyone ask about the biblical borders of the Promised Land. I know of no politician who pursues an agenda of translating prophecies of the Bible concerning the borders into political reality. However, I come across Christians with the question of when the state of Israel will reach its biblical borders. And in past years, secular journalists and political analysts have given publically thought to whether certain Israeli politicians dreamed of a “Greater Israel within biblical borders”. It is therefore appropriate to outline what the Bible actually says about the borders of the Promised Land.” Read more.. […]